Philips Romeo Table Lamp – 1960s Advertisement

It’s nice to play here…

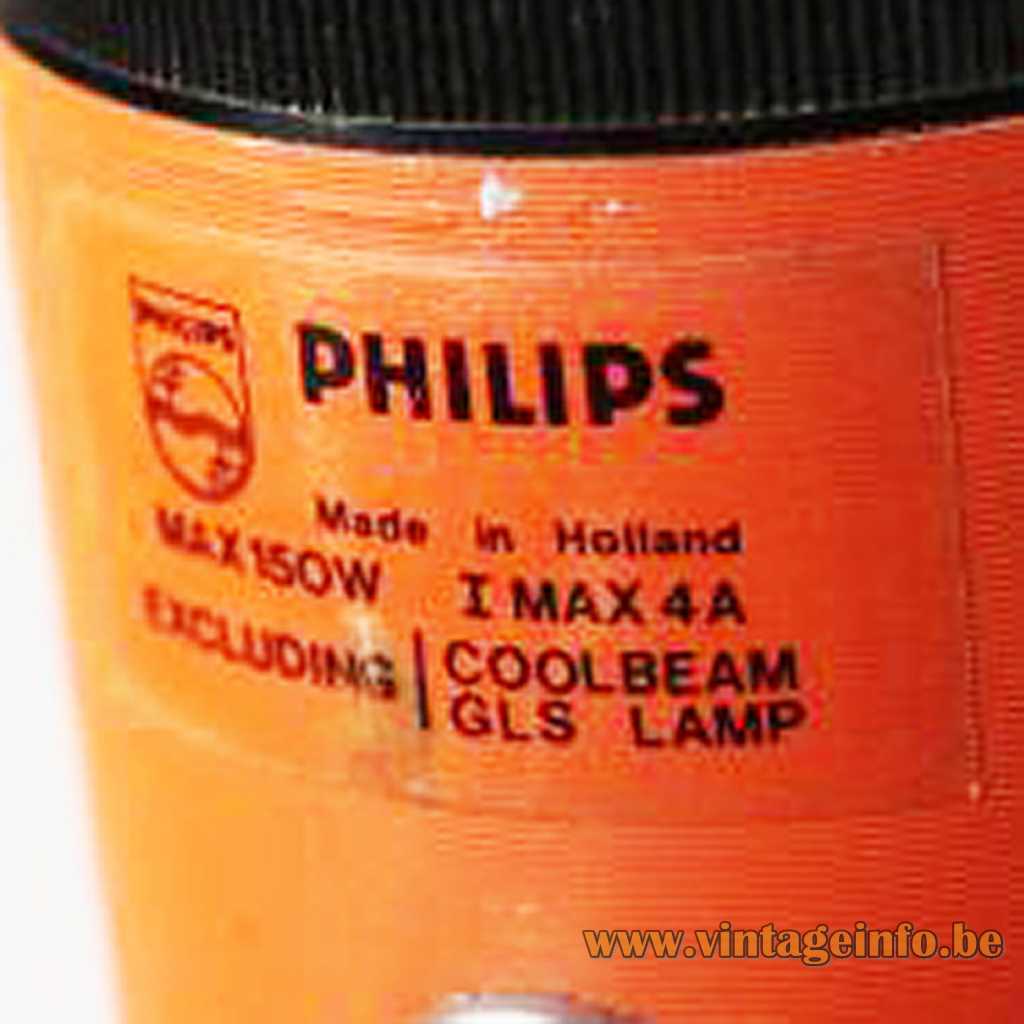

Philips Romeo Table Lamp – Labels

Labels on the box that the lamp was packed in.

Left: Philips N.V. Brussel: Made in Brussels, Belgium

Right: Romeo Kopspiegellamp (dutch): silver tipped light bulb.

Lamps In The Movies!

Upgrade (2018)

A Philips Romeo table lamp was used as a set decoration in the “cyberpunk action body horror” film Upgrade from 2018. A futuristic thriller with Logan Marshall-Green.

Unit 42 (2017)

A Philips Romeo table lamp was used as a set decoration in the in the 2017Belgian television series Unit 42. Starring Patrick Ridremont, Constance Gay and Tom Audenaert. Many other lamps appear in the series.

Links (external links open in a new window)

Philips history on the Philips website

The story about the Philips logo

Unité 42 (2017) TV Series – Wikipedia

Unité 42 (2017) TV Series – IMDb

Vintageinfo

Many Thanks to Ger for the pictures.

Many thanks to Storm from Storm Vintage for the help.

Philips Romeo Table Lamp

Materials: Black painted round flat base with a built-in switch. Cast iron counterweight inside the base. Philips logo stamped in the base. Folded brass rod and parts. Black painted aluminium UFO style mushroom lampshade with a whole in the middle. Painted white inside. Bakelite E27 socket.

Height: 41,5 cm / 16.33”

Width: ∅ 28,5 cm / 11.22”

Base: ∅ 11,5 cm /4.52”

Electricity: 1 bulb E27, 1 x 100 watt maximum, 110/220 volt.

Any type of light bulb with an E27 socket can be used. For this lamp preferable a silver tipped light bulb for the down-light effect.

Period: 1960s – Mid-Century Modern.

Designer: To be appraised.

Manufacturer: S.A. Philips N.V., Brussels, Belgium.

Other versions: The Philips Romeo table lamp comes in several colours. Slight differences in the lampshade, rod and base.

Often called the Z-lamp, because of the curved stem.Other Philips lamps are called Z-lamps online, but in reality, they all have different names.They were never called Z-lamps by Philips.

The later Romeo version from the 1970s, with a grounding connection, is called the Romeo 69.

The Philips Romeo table lamp is based on a design from the 1950s, the Junior table lamp. It is its successor.

Philips Romeo Table Lamp – Made In Belgium

Philips had several factories in Belgium where desk and table lamps were made. This lamp is definitely one of them. Presumably, most lamps with a similar design were produced in Belgium. The ministries in Brussels were full of them; there was one on every desk.

Koninklijke Philips N.V.

Inspired by the fast-growing electricity industry and by the promising results of Gerard Philips’ own experiments with reliable carbon filaments, his father, the Jewish banker Frederik Philips from Zaltbommel, financed the purchase of a small factory in Eindhoven, the Netherlands, on 15 May 1891.

The first years were difficult and the company was close to bankruptcy, but in 1895 Gerard’s younger brother Anton Philips joined the firm. With Anton’s commercial drive the family business expanded very quickly and the Philips brothers turned the lamp factory into the basis of what would become a major international electronics company.

To secure the supply of lamp parts, Philips very early started to make things in-house: its own machines, its own glass (from 1916) and even its own gas separation to fill lamps with argon, so it was less dependent on German suppliers during wartime. This strong vertical integration became typical for Philips and later also supported radio and medical products.

From the 1920s onward Philips did not only make lamps but also radios and even ran its own shortwave stations (PCJ and PHOHI) to promote them worldwide – an early mix of product and broadcasting.

In later sources the “first Philips shaver” is sometimes put in the early 1930s, but Philips itself dates the electric Philishave to 1939; in any case it shows how the company moved from lighting into small household and personal devices.

On 9 May 1940, the day before the German invasion, the Philips family left for the United States with a large part of the company’s capital. From there they continued operations as the North American Philips Company and kept control over the group during the war. After 1945 the headquarters returned to the Netherlands, again in Eindhoven.

After the war Philips became a broad technology group: radios, televisions, X-ray and medical equipment, and of course lighting, which remained one of its core businesses for decades. Only much later, in 2016, the lighting activities were split off and continued under the name Signify – all vintage Philips luminaires on this site belong to the period when lighting was still an integral part of Philips.

Today Philips is mainly a health-technology company. The roots are still in Eindhoven, but since 2025 the head office is in Amsterdam (Prinses Irenestraat 59).

Louis Christiaan Kalff (1897–1976)

Louis Kalff (Amsterdam, 14 November 1897 – Waalre, 16 September 1976) was the designer and art director who, more than anyone else, gave Philips a modern visual identity in the 1920s and 1930s. From 1925 onwards he worked at the Philips advertising department in Eindhoven, where he was asked to make the company’s advertising and presentation match the size and ambitions of the firm.

Philips house style and logo

When Kalff arrived, the name “Philips” was written in many different ways. He standardised the lettering, the colours (he liked strong primary colours) and the overall layout of advertisements and packaging. In the second half of the 1920s he introduced the combination of waves and stars as symbols for radio transmission, first on packaging and later on products. In 1938 he brought the wordmark and the emblem together in the familiar Philips shield – one of his best-known contributions.

Besides the work for Philips he designed posters and graphic work for the Holland-America Line, Calvé, Zeebad Scheveningen, Holland Radio and others, always in the same clear, modern idiom.

Lighting and the LIBU (1929)

Because electric lighting in architecture was developing very fast, Kalff founded the Lichtadviesbureau (LIBU) in 1929. That bureau advised architects, municipalities and companies on how to use light in buildings, shops and public space. It did not only push Philips products, it also looked at what the market needed. Through the LIBU, Kalff organised the lighting for several world exhibitions, among them Barcelona, Antwerp and Paris.

From advertising to industrial design

After the Second World War the earlier “artistic propaganda” work inside Philips evolved into a broader industrial design service, later known as ARTO. Kalff was closely involved in this and for years he supervised the styling of radios, loudspeakers, domestic appliances and professional lighting installations. New products were often “kalfft” first – checked for function, for looks and for recognisability as a Philips product.

Did he design the Philips lamps?

Many 1950s Philips lamps are offered today as “Louis Kalff”. That sounds attractive, but it is not supported by Philips documentation. Kalfforganised the lighting and design departments (LIBU, later ARTO), he approved designs and he set the taste, but there is no primary source that attributes specific desk, table or other lamps to him personally. The similarity between his later architectural work (Evoluon) and some saucer-shaped Philips lamps, such as the Decora, Senior and Junior, simply shows that the same visual language was used inside Philips.

The story that he also designed lamps for German makers such as Cosack / Gecos is another internet repeat and has, as far as we know, no documentary basis.

Safer wording: “Philips lighting of the 1950s was developed within the design organisation created and led by Louis Kalff, but no individual lamp models can be firmly attributed to him.”

Architecture and later work

Next to graphic work Kalff also designed and co-designed buildings for Philips, such as the Dr. A.F. Philips Observatory in Eindhoven (1937) and houses for Philips directors. After his retirement in 1960 he remained active as advisor and architect. His best-known late project is the Evoluon in Eindhoven (opened 1966), designed with Leo de Bever, a futuristic disc-shaped building that perfectly fits the forward-looking image he had promoted at Philips for four decades.

Louis Kalff passed away in Waalre on 16 September 1976.

Philips Romeo Table Lamp – Box

The box that the lamp was packed in. Complete with a 100 watt silver tipped light bulb, bigger than the 60 watt bulbs, so that a piece of the silver part of the bulb just sticks out above the lampshade. To achieve the same effect today, the E27 bulb socket inside would have to be positioned higher for a modern, smaller LED bulb.