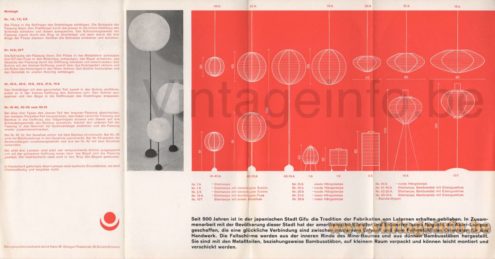

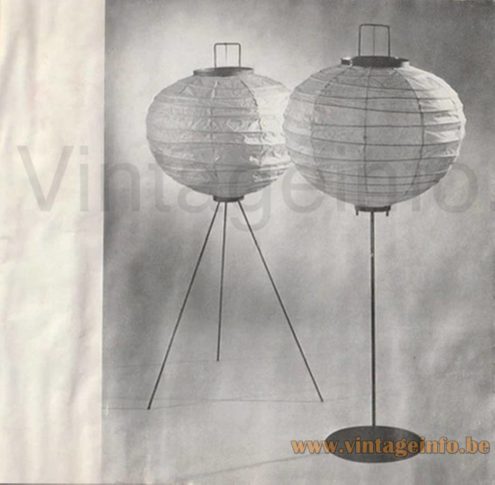

Akari Tripod Floor Lamp – 1960s Catalogue Picture

German leaflet with all available Akari lamp models: table lamps, floor lamps and pendant lamps.

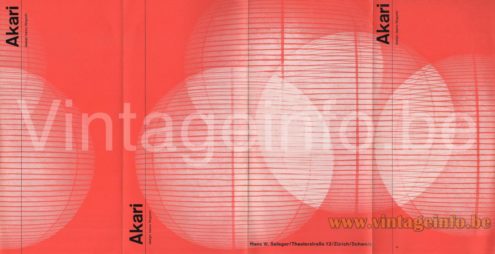

Akari Tripod Floor Lamp – 1960s Catalogue Picture

German leaflet front page.

Early 1950s Akari vs. later productions

Early Akari lamps from the 1950s differ noticeably from later editions. The washi paper used in the first Gifu productions is thinner, warmer in tone and more irregular, giving the light a softer and more organic glow. The bamboo structure is lighter and less standardized, reflecting the experimental nature of Noguchi’s earliest designs. These lamps were made in small numbers, before Akari became an established product line, and long before later re-editions and international distribution.

From the 1960s onwards, Akari lamps were produced in larger series, with more standardized forms and materials to ensure consistency and durability. While later versions remain faithful to Noguchi’s original concept and are still handcrafted in Gifu, early examples from the 1950s are exceptionally rare and are today primarily found in museum collections or long-held private stocks.

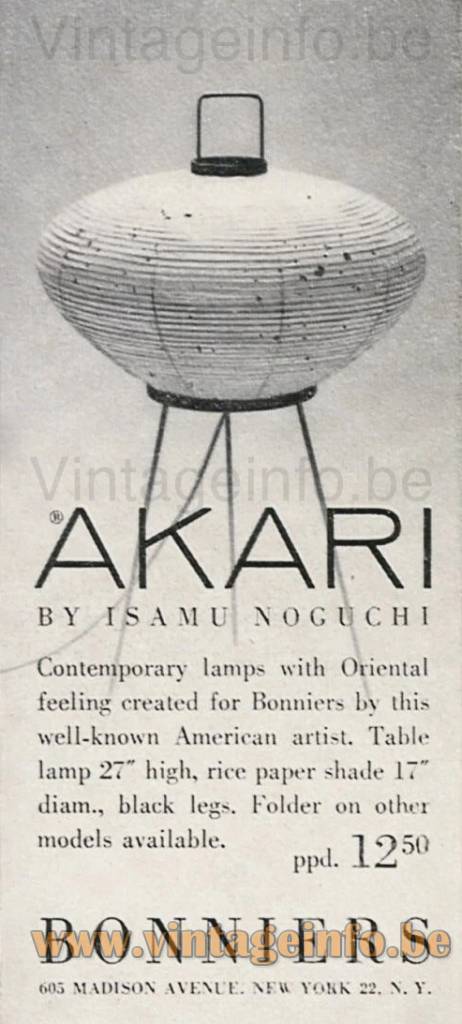

Akari Tripod Floor Lamp – 1958 Bonniers Advertisement

A 1958 publicity by the New York based company Bonniers.

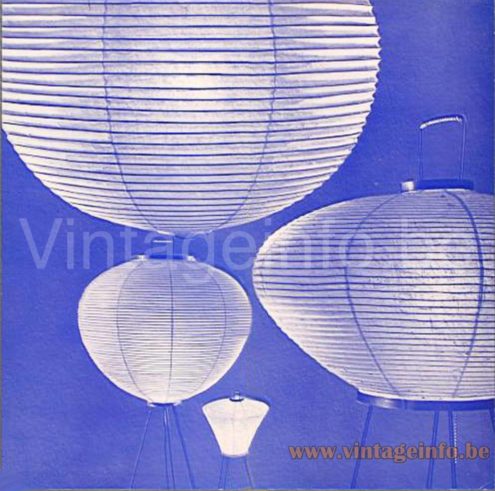

Akari Tripod Floor Lamp – George Kovacs Catalogue Picture

Catalogue picture of the American brand George Kovacs.

Akari Tripod Floor Lamp

Materials: 3 thin black painted welded metal legs. Paper globe lampshade with 2 wooden rings. Bakelite E27 socket.

Height: 125 cm / 49.21”

Width: ∅ 55 cm / 21.65”

Electricity: 1 bulb E27, 1 x 60 watt maximum, 110/220 volt.

Any type of light bulb can be used, not a specific one preferred.

Period: 1950s – Mid-Century Modern.

Designer: Isamu Noguchi.

Manufacturer: Ozeki & Co Ltd, Japan.

Other versions: This Akari tripod floor lamp comes in a few varieties. Many comparable lamps were made.

In the United States, these lamps were marketed and distributed by George Kovacs and Bonniers, both based in New York, among others. American distributors were instrumental in positioning Akari within the rapidly expanding modern design market of the 1950s and 1960s. Through design showrooms, interior architects and high-end retailers, the lamps were introduced not merely as functional lighting, but as sculptural objects aligned with contemporary architectural ideals. Their commercial success abroad significantly contributed to the international recognition of Isamu Noguchi‘s work and reinforced the global appeal of Japanese modernism during the post-war decades.

Isamu Noguchi

Isamu Noguchi (1904–1988) was a Japanese-American sculptor, designer and landscape artist whose work consistently blurred the boundaries between art, design and architecture. Born in Los Angeles to an American mother and a Japanese father, Noguchi grew up between cultures—a duality that would profoundly shape his artistic vision throughout his life.

After initially studying pre-medical sciences, Noguchi chose the path of art and in 1927 moved to Paris to work in the studio of Constantin Brancusi. This formative period sharpened his understanding of pure form and material, ideas that would remain central to his work. Extensive travels during the 1920s and 1930s further expanded his outlook, exposing him to traditional crafts, ancient landscapes and non-Western concepts of space.

Although Noguchi began as a sculptor, he rejected rigid definitions of artistic disciplines. “Everything is sculpture,” he famously stated, considering any material or idea shaped in space to belong to sculpture. This philosophy led him to work across an extraordinary range of fields: stone and metal sculpture, furniture, lighting, stage sets and landscape design.

From 1935 onwards, Noguchi collaborated extensively with modern dance pioneer Martha Graham, designing more than twenty stage sets. These environments were conceived as active sculptural elements, enhancing movement and drama rather than serving as mere backdrops. Light, space and motion became inseparable components of his artistic language.

Noguchi’s engagement with light as a sculptural medium deepened during and after the Second World War. Earlier experiments with internally illuminated sculptures—such as Lunar Infant—can be seen as direct predecessors of his later lighting designs. For Noguchi, light was not just functional illumination, but an emotional and spatial force, capable of transforming environments and human experience.

In parallel with his sculptural practice, Noguchi created influential furniture designs, including the glass-topped coffee table for Herman Miller and the Cyclone dining table for Knoll. These works share the same organic, sculptural logic found in his art.

By the time of his death in 1988, Noguchi had established himself as one of the most original and multidisciplinary figures of twentieth-century design. Today, his work is represented in major museum collections worldwide, and his ideas continue to influence contemporary art, design and architecture.

Akari Tripod Floor Lamp – 1950s Catalogue Picture

Akari Light Sculptures – Company & Production

The Akari light sculptures were conceived by Isamu Noguchi in 1951, following a visit to the city of Gifu, Japan—a region renowned for its centuries-old tradition of lantern making using bamboo and mulberry bark paper. During this visit, Noguchi was invited to help modernise the traditional paper lantern and introduce it to an international audience.

Noguchi named his creations Akari, a Japanese word meaning “light” or “illumination,” but also suggesting lightness and weightlessness. The written characters combine the symbols for sun and moon, perfectly reflecting Noguchi’s intention: to transform harsh electric light into something warm, natural and atmospheric, akin to sunlight filtered through shoji screens.

Since their inception, Akari lamps have been produced in Gifu by Ozeki & Co., a manufacturer specialising in traditional lantern craftsmanship. Production has remained continuous since 1951 and still follows largely unchanged, hand-crafted methods. Each lamp begins with the making of washi paper from the inner bark of mulberry trees. Bamboo ribs are stretched over carefully carved wooden moulds, forming the sculptural framework. Strips of washi paper are then glued to both sides of the structure.

Once dried, the internal wooden mould is removed, leaving a resilient yet lightweight paper form. This construction allows the lamps to be collapsed and packed flat for transport—an elegant fusion of practicality and poetry. When assembled, the paper softly diffuses the light source, eliminating harsh shadows and creating an even, ambient glow.

Noguchi deliberately avoided calling Akari “lanterns,” seeing them instead as light sculptures. Their forms range from traditional spherical shapes to elongated, angular, zigzagging or cloud-like silhouettes. Over time, more than 100 different Akari models have been introduced, including pendant, table and floor lamps, as well as the later UF series developed in the 1980s.

Initially, Akari lamps were met with scepticism in Japan, where critics considered them distorted versions of traditional Gifu lanterns. However, international recognition soon followed, and the lamps gradually became icons of modern design. Their combination of traditional materials, modern form and timeless warmth has ensured their lasting relevance.

Today, Akari lamps are still handmade by Ozeki & Co. in Japan and are distributed worldwide, remaining one of the clearest examples of how traditional craftsmanship can be reinterpreted through modern design without losing its cultural essence.

Akari Tripod Floor Lamp – 1950s Catalogue Picture

On this page: model 10A, the tripod floor lamp and model 10F, a one rod floor lamp.

Many thanks to Max from AfterMidnight for all the pictures.

Many thanks to Max for the catalogue pictures. Another Max.;)